“Extraordinary. . . . An elegant mixture of case history and street-level observations of the struggles of those afflicted with visual disorders.”

— San Francisco Chronicle

The Mind’s Eye

“The effects of a profound perceptual deprivation such as blindness may cast an unexpected light on these questions. Going blind, especially later in life, presents one with a huge, potentially overwhelming challenge: to find a new way of living, of ordering one’s world, when the old has been destroyed.” —Oliver Sacks

In The Mind’s Eye, Oliver Sacks tells the stories of people who are able to navigate the world and communicate with others despite losing what many of us consider indispensable senses and abilities: the power of speech, the capacity to recognize faces, the sense of three-dimensional space, the ability to read, the sense of sight. For all of these people, the challenge is to adapt to a radically new way of being in the world.

There is Lilian, a concert pianist who becomes unable to read music and eventually even to recognize everyday objects; and Sue, a neurobiologist who has never seen in three dimensions, until she suddenly acquires stereoscopic vision in her fifties.

There is Pat, who reinvents herself as a loving grandmother and well-loved member of her community, although she has aphasia and cannot utter a sentence; and Howard, a prolific novelist who must find a way to continue his life as a writer even after a stroke destroys his ability to read.

And there is Dr. Sacks himself, who tells the story of his own eye cancer and the bizarre and disconcerting effects of losing vision to one side.

Sacks explores here some very strange paradoxes–people who can see perfectly well but not recognize their own children, blind people who become hyper-visual, or who navigate by “tongue vision.” Along the way, he considers more fundamental questions: How do we see? How do we think? How important is internal imagery—or vision, for that matter? Why is it that, although writing is only 5000 years old, humans have a universal, seemingly innate, potential for reading?

The Mind’s Eye is a testament to the complexity of vision and the brain and to the power of creativity and adaptation. And it provides a whole new perspective on the power of language and communication, as we try to imagine what it is to see with another person’s eyes, or another person’s mind.

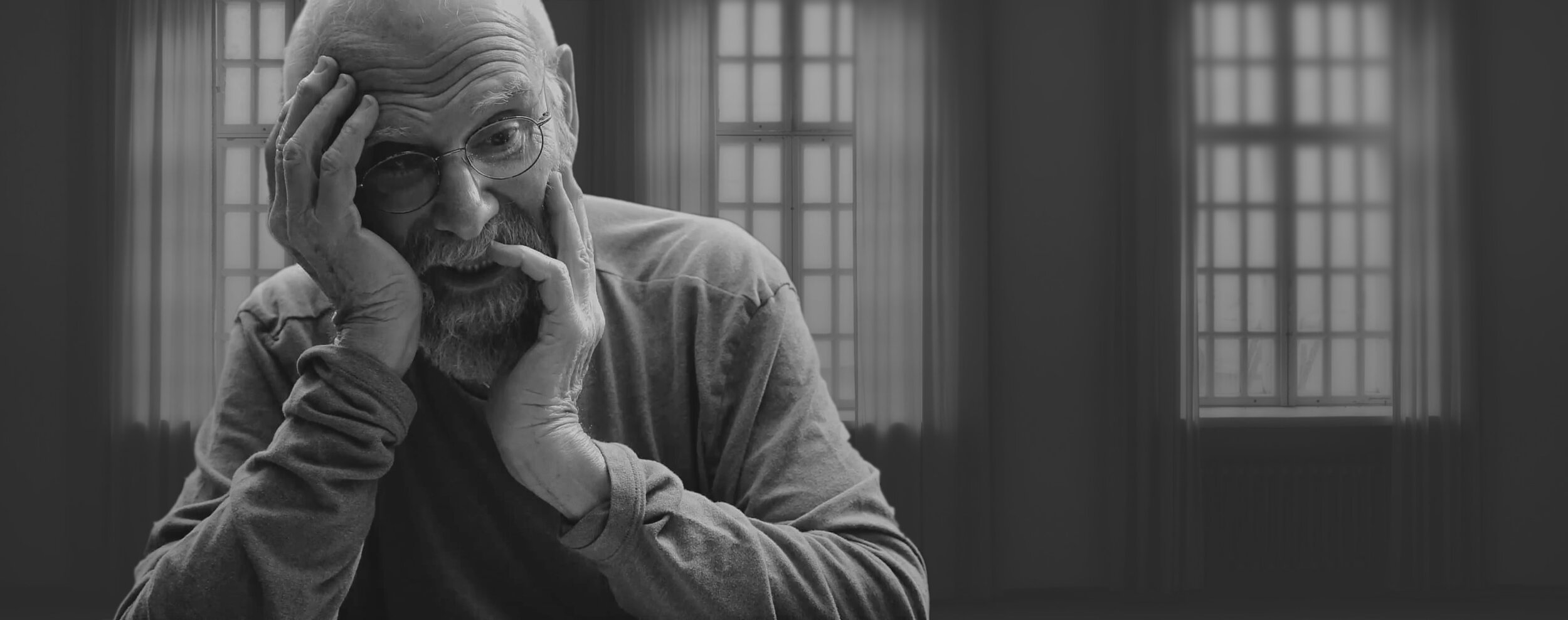

📷 The ever-curious Oliver Sacks involved in one of his usual activities—investigation. Photo by Bill Hayes

Praise for The Mind’s Eye

“Is there anyone who’s done more to elucidate the ability in disability than Oliver Sacks?. . . . In Sacks’ world, even with great loss there are fascinating compensations.” —People

“Another masterpiece of phenomenological description by our most gifted and humane chronicler of neurological disorders. . . . Sacks effortlessly blends his teaching of neurology with the most sensitive descriptions of the ways in which our individual brains yield the most extraordinary variety of human experience.” —New Scientist

“Frank and moving. . . . His books resonate because they reveal as much about the force of character as they do about neurology.” —Nature

“Rich with the sort of observation and insight that makes Sacks’s writing satisfying. . . . Sacks shows us knowledge, discipline, and imagination confronting the terrors of illness and loss. . . . Readers may never take the view of a sunrise or of their child’s smile the same way again.” —Boston Globe

“Elaborate and gorgeously detailed. . . . Again and again, Sacks invites readers to imagine their way into minds unlike their own, encouraging a radical form of empathy.” —Los Angeles Times